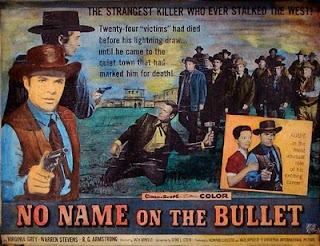

John Gant (Audie Murphy) rides into a quiet little town and spreads fear and panic. How does he do this? By taking a room at the hotel, drinking countless cups of coffee and playing the odd game of chess.

What terrifies the townsfolk is not Gant’s behaviour but his reputation. He is reputed to have killed thirty men, and he’s killed them all for money. He is not a wanted man. He has never been convicted of a crime. He is always able to persuade his victims to fight, in front of witnesses, and all his killings have technically in self-defence.

Almost every man in town is convinced that Gant has come to kill them. Every man has at least one enemy.

Pretty soon there are a lot of frightened men doing crazy things and becoming severely paranoid. A paranoia that can even lead to a man killing himself. A man who never was Gant’s intended victim. It can lead frightened men to start killing each other. It can tempt normally sane men to consider vigilante justice. The town is being torn apart.

The sheriff has no clue what to do. He can’t order Gant to leave town. The man has committed no crime.

The town’s do-gooder doctor Luke (Charles Drake) feels that he has to do something to stop the madness but he has no idea how to do it.

The idea of a hired killer who taunts his victims into drawing first and then guns them down was far from original but it is used here in an original way, and having such a cold-blooded killer as the protagonist, played by a very popular star, was certainly daring.

Audie Murphy was a war hero who had a troubled life, having never fully recovered from his wartime experiences. It’s ironic that he become so revered as a war hero, given that his wartime military service to a certain extent wrecked his life. He’s not generally all that highly regarded as an actor and is usually dismissed as a guy who really wasn’t much good in anything but westerns. His performance here suggests that there was more to him than that. He may have had a limited range as an actor but he certainly knew how to project menace in an impressively subtle way. He really does make John Gant seem very very dangerous, but without doing anything overt. This is a guy who terrifies people by sitting around drinking coffee and playing chess.

What is really impressive is that Murphy manages to make us like Gant. We care what happens to him.

Gant justifies his work by arguing that all the men he killed deserved killing. If someone hires a killer to kill a man then that man has probably done something pretty bad, and society might well be better off without him. Gant has the psychology of a 20th century hitman rather than a Wild West gunfighter. He kills scientifically and goes to incredibly elaborate lengths to ensue than no innocent bystander gets hurt. Gant kills for money, not because he likes killing. It’s just a job.

Luke can’t help liking him as well.

The ending is rather clever. The film was of course constrained by the Production Code but it gives us an ending that is not quite the predictable Production Code ending that we expect. There’s a nice ouch of ambiguity.

There are a few speechifying moments and Luke gets a bit tiresome with his self-righteousness.

Gene L. Coon’s screenplay is however intelligent and fairly complex. It throws some moral and ethical dilemmas at us without suggesting that there are easy answers. Even Luke’s self-righteousness gets shaken a little.

Director Jack Arnold was renowned as a director of 1950s science fiction movies that were usually a cut above the usual run of such movies.

It often amuses me when people talk about how revolutionary the so-called revisionist westerns of the late 60s and 70s were. There’s really not a single revolutionary thing in those movies that isn’t to be found in the classic Hollywood westerns of the period from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. If there was a clever twist that could be given to classic western themes then John Ford, Howards Hawks, Anthony Mann or Budd Boetticher had almost certainly already thought of it. Moral ambiguity, flawed heroes, tortured heroes, ethical dilemmas, sympathetic portrayals of Native Americans, a questioning of the mythology of the Wild West - the old masters of the genre had given us all of these things.

And in No Name on the Bullet we get a genuine anti-hero.

Universal’s Region 1 DVD offers a very pleasing 16:9 enhanced transfer (the movie was shot in colour and in the Cinemascope aspect ratio).

I watched this movie based on a glowing recommendation at Riding the High Country.

No Name on the Bullet is an excellent grown-up western with an extraordinary charismatic performance by Audie Murphy. Highly recommended.

I watched this movie based on a glowing recommendation at Riding the High Country.

No Name on the Bullet is an excellent grown-up western with an extraordinary charismatic performance by Audie Murphy. Highly recommended.